Remote Sensing Journal – Special Issue

Special Issue Editor

Guest Editor

Interests: flow hydraulics; sediment transport processes; ecohydrology; remote sensing

Special Issue Information

Dear Colleagues,

The primary lens of ecohydrology is focused on understanding the distribution and abundance of biota in the context of how and why organisms are dependent on specific biophysical space (habitat) to complete one stage or another in their life cycles. Unfortunately, the spatial distribution and abundance of aquatic habitat is the least empirically quantified attribute of rivers and streams. This may be in part because little advancement has been made towards using remote sensing to assess flow velocity which is a requirement for defining aquatic habitat.

Development and application of remote sensing tools geared toward quantifying flow velocity could greatly enhance ecohydrological understanding of fluvial systems. This is especially true for regulated systems in need of environmental flow analysis aimed at minimizing harm to aquatic organisms from fish to rare plants through flow regulation by dam control or irrigation withdrawal.

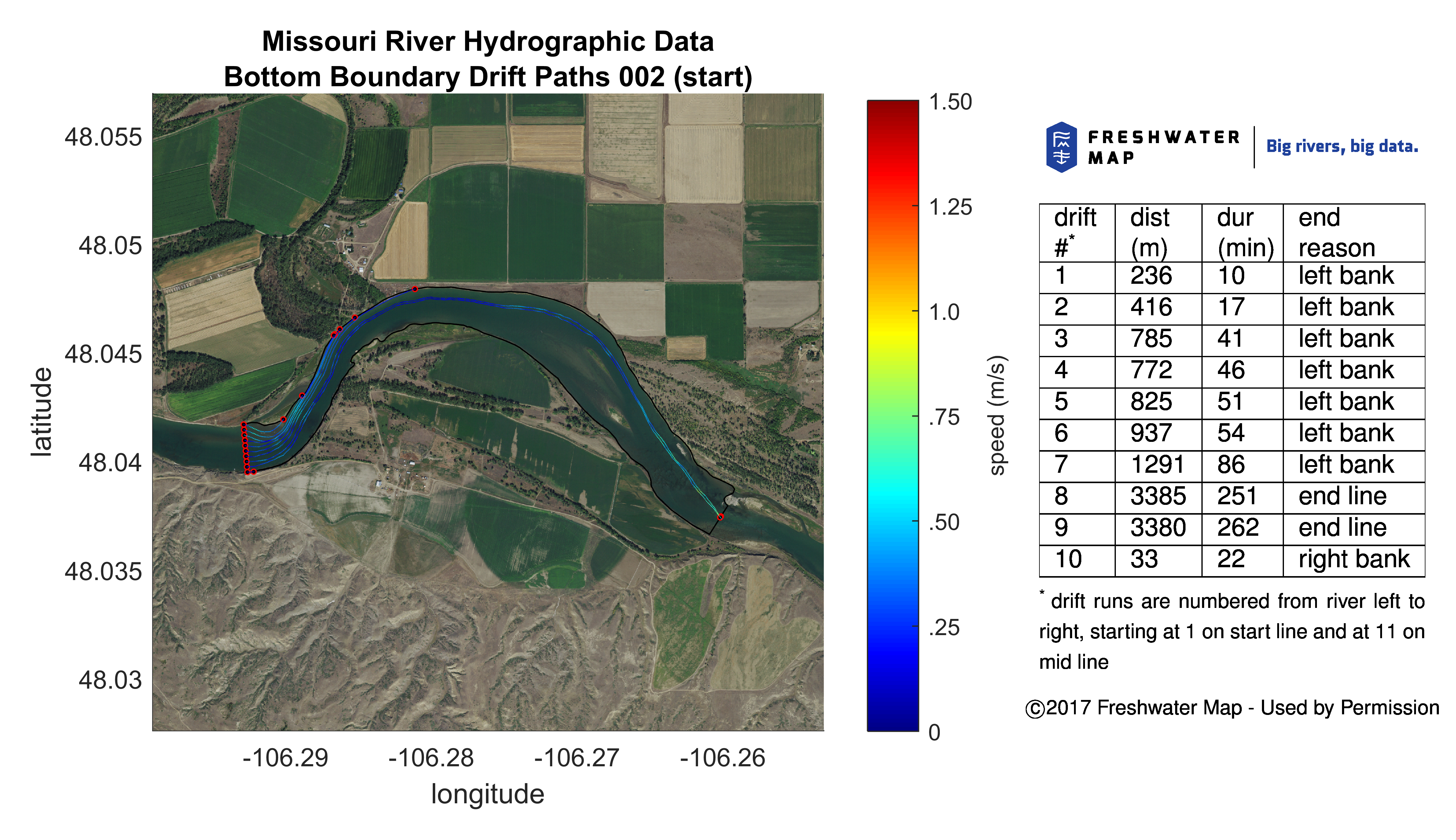

New advances in hydro-acoustic river mapping, an emerging form of remote sensing of fluvial systems, allows direct empirical measurement of flow from the site scale to the river corridor scale covering 100’s of km. This approach should be linked to more traditional forms of aerial and satellite remote sensing of fluvial systems that have focused on the assessment of channel bathymetry, widths, depths, slopes, plan form complexity, substrate composition, surface water temperatures, and composition of riparian vegetation.

The focus of this special issue will be publishing studies that are striving to use and combine various forms of remote sensing to measure flow and discharge in rivers to better enhance our understanding of rivers in light of climate change and environmental flow management.

Dr. Mark S. Lorang

Guest Editor

Manuscript Submission Information

Manuscripts should be submitted online at www.mdpi.com by registering and logging in to this website. Once you are registered, click here to go to the submission form. Manuscripts can be submitted until the deadline. All papers will be peer-reviewed. Accepted papers will be published continuously in the journal (as soon as accepted) and will be listed together on the special issue website. Research articles, review articles as well as short communications are invited. For planned papers, a title and short abstract (about 100 words) can be sent to the Editorial Office for announcement on this website.

Submitted manuscripts should not have been published previously, nor be under consideration for publication elsewhere (except conference proceedings papers). All manuscripts are thoroughly refereed through a single-blind peer-review process. A guide for authors and other relevant information for submission of manuscripts is available on the Instructions for Authors page. Remote Sensing is an international peer-reviewed open access semimonthly journal published by MDPI.

Please visit the Instructions for Authors page before submitting a manuscript. The Article Processing Charge (APC) for publication in this open access journal is 2400 CHF (Swiss Francs). Submitted papers should be well formatted and use good English. Authors may use MDPI’s English editing service prior to publication or during author revisions.

Keywords

- aquatic habitat

- flow velocity

- discharge from space

- ecohydrology

- climate change

- hydro-acoustic remote sensing

- environmental flow analysis